IVY: A Shared Virtual Memory System for Parallel Computing

Introduction

In this paper, we are introduced to IVY, a shared virtual memory system for parallel computing. Published in 1988, IVY was a concept designed for a single token ring topology that was implemented in Apollo workstations. The main idea was to evaluate if shared memory was a better alternative than a memory passing system, especially with loosely coupled microprocessors since there hadn’t been enough work done at the time.

Rather than relying on message passaging, this new architecture coupled with IVY allowed for simultaneous use of virtual memories on processes happening in parallel processors. This approach highlights how shared virtual memory in parallel programs can exploit capabilities that aren’t feasible in memory passing.

Shared Memory vs. Memory Passing

Memory passing is done through an interprocess communication, which does not use global data and relies on programmers to handle the memory passing through send and receive in parallel programs. This is not ideal as the communication process is slow and inefficient for process migration and handling complex data structures. These complications come from having multiple address spaces, which shared memory gets rid of. This in turn has no problem passing complex data structures as the shared memory address can be passed around using pointers. For parallel programming in a multiprocessor system, shared memory is the ideal memory system to implement.

Implementation

The implementation setup is established on the Apollo domain, an integrated system composed of workstations and servers connected in a ring topology. In this setup, IVY has 5 modules. These include process management, memory allocation, initialization, remote operation, and memory mapping. A key part of this implementation is the virtual memory address, a single address space that will be shared by all the processors.

The address then gets partitioned into read only pages and write pages. Read only pages can exist on any node while write pages can only exist on one node. The memory mapper handles the read and write operations with three algorithms: the centralized manager, the fixed distributed manager, and dynamic distributed manager.

When it comes to process management, IVY implements process control blocks (PCBs), which store information such as process state that are used for process migration and scheduling. This data structure implementation helps to simplify process migration and synchronization. For memory allocation, IVY uses a single level allocator. The authors do point out that a two level memory management approach would be more efficient, as this module only lets one processor allocate memory at a time.

The remote operation module enables remote communication between the other modules in IVY. It uses a remote procedural call (RPC) to broadcast requests across the network and get responses, as well as forwarding requests from one processor to another. IVY is written in Pascal, which means programmers need to account for the nature of pascal procedure calls when implementing the system. It’s essential that programmers and compilers define what’s shared memory as well as private memory.

Results

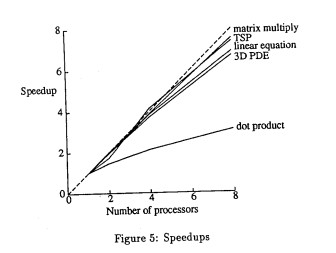

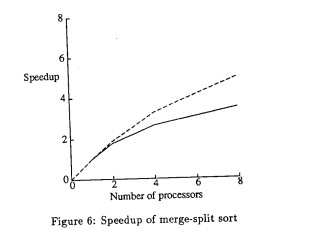

IVY is written in Pascal, and so are the experiments that were done to test for side effects in shared data structures as well as its granularity in parallelism. The first two experiments involve pascal programs of jacobi algorithms that solve linear equations and 3D partial differential equations. Other programs include the traveling salesman problem, matrix multiply, dot product, and split-merge sort. The results shown in figures 5 and 6 of the paper, we find that both split-merge sort and dot product tests do not yield linear speedups. As for the other programs, we find that the linear speedup increases when multiple processors are introduced. Multiprocessors have more memory, which means it will handle less page faults and have a better yield.

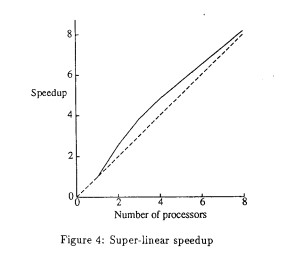

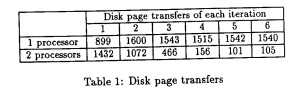

Another interesting point is that sometimes IVY achieves super-linear results, as shown in the following figure. This can be attributed to the low memory size of the uniprocessor that the IVY system was compared to - because of this low memory size, the uniprocessor was unable to hold all of a given algorithm’s (e.g., large matrix multiplication) page tables within memory, leading to huge performance losses in swapping pages from disk to memory. With IVY, since there were multiple processors being used, these algorithms could be stored in memory without swapping to disk - this leads to superlinear performance in the case of IVY. Proof of this large amount of page swapping is shown in Table 1. Of note is that if IVY was tested today, it likely would not have achieved superlinear results because of much larger standard memory capacities.

Weakness

This paper has several weaknesses, but a notable one is the lack of comparison with memory passing. The paper makes a case for shared virtual memory, but it would’ve been insightful to see a performance difference to establish further validity. Another weakness is that the memory allocation is single level, which means only one processor can allocate memory at a time. Even the paper itself notes it would be more efficient to implement a two level memory management approach. Another weakness is that the high overhead of IVY is caused by its implementation in user mode, rather than system mode . As mentioned in the results, the split-merge sort and dot product tests did not yield a linear speed-up, which could come from bottlenecks such as the single level memory allocator as well as its high overhead.

Class Discussion

Is Pascal a Dead Language?

No, Pascal is not entirely dead—it continues to influence modern programming languages, particularly Java. One of Pascal’s most significant contributions was its p-code (pseudo-code) virtual machine, which was the first implementation of bytecode execution. Although Java does not use p-code directly, its Java Virtual Machine (JVM) is conceptually similar, operating as a stack-based execution environment much like Pascal’s VM.

When Java was developed, its creators aimed for object orientation and platform portability, leading them to adopt and extend ideas from Pascal’s virtual machine. In a way, Java’s runtime environment can be seen as an evolution of concepts pioneered by Pascal’s p-code system.

User Mode in Ivy

Ivy operates in user mode, as mentioned on page 95 of the paper, where it describes its prototype implementation.

This raises the question: Was Ivy implemented as a shared library? While the paper does not explicitly state this, the fact that Ivy runs in user mode suggests that key functionalities, such as memory management and page handling, were likely provided via user-space libraries rather than kernel modifications.

One critical aspect of Ivy’s design is its page fault handling. The system provides a user-space page fault handler, meaning that when a page fault occurs, it is handled at the user level instead of being immediately processed by the operating system’s kernel. This is similar to mechanisms in modern Linux, where page fault handlers can be invoked in user space, a feature often used in networking and distributed systems to manage memory more efficiently.

The Apollo page fault handler played a crucial role in Ivy’s implementation, allowing the system to intercept memory access requests and manage them at the application level. This approach provided flexibility but also introduced performance trade-offs, as user-space page fault handling is generally slower than direct kernel-managed memory operations.

What is a Centralized Manager in Ivy?

In Ivy, a centralized manager is responsible for coordinating shared memory access and ownership changes between processors.

When a processor (Processor A) needs access to a shared memory page, it must first interact with the centralized manager. The manager performs several key functions:

-

Checks the virtual-to-physical mapping to determine whether the requested page is already available on the requesting processor.

-

Handles invalidations and ownership transfers if the page is currently owned by another processor.

-

Ensures consistency by enforcing memory coherence rules across multiple nodes.

If a requested page is not locally available, the centralized manager identifies the current owner of the page, facilitates its transfer, and invalidates other copies if necessary. This ensures that only one writable copy of a page exists in the system at any time.

While this approach simplifies memory management, it introduces a potential bottleneck, as all processors must communicate with a single entity to request pages, leading to scalability concerns in larger systems.

Where is the Code for Ivy?

The original Ivy implementation was developed in the late 1980s, but its source code was not publicly released, as was common practice at the time.

However, similar implementations have been developed based on Ivy’s protocol, including:

-

LibDSM – A modern distributed shared memory (DSM) library that incorporates some of Ivy’s concepts.

-

Giant – An implementation that directly uses the Ivy protocol to provide shared virtual memory.

Although Ivy itself is not readily available, these projects serve as useful references for understanding and experimenting with distributed shared memory systems based on Ivy’s architecture.

Apollo Domain OS vs. Unix

Apollo developed its own proprietary operating system called Domain/OS, which was designed specifically for networked workstations and featured built-in support for distributed computing. Unlike Unix, which was widely adopted and evolved into various open-source and commercial distributions, Domain/OS was a niche system tailored to Apollo hardware.

However, Hewlett-Packard (HP) acquired Apollo in 1989 and eventually discontinued Domain/OS, favoring Unix-based systems instead. This marked the end of Apollo’s independent operating system, as HP integrated Apollo’s technology into its own Unix-based platforms before phasing out Domain/OS entirely.

Superlinear Scaling and Memory Considerations in Ivy

Superlinear Scaling Observations

The Ivy paper highlights superlinear speedup for large matrix sizes, particularly in Figure 4, to demonstrate its performance benefits. This effect is likely due to reduced page faults as more processors increase the available memory pool, improving data locality. However, smaller matrices did not exhibit the same superlinear speedup, as their working set sizes were small enough to fit within a single processor’s cache, limiting the benefits of shared memory.

Why Examine System Capabilities?

The paper explores Ivy’s capabilities in order to address page thrashing and memory efficiency—critical factors in distributed shared memory (DSM) systems. This discussion ties into modern research on far memory and disaggregated memory, where memory is physically separated from compute nodes but accessed as if it were local, potentially reducing page migration overhead.

Shared Memory and Memory Utilization

One important question not fully addressed in the paper is: How much memory is saved due to sharing? Ivy’s shared memory model allows multiple processors to access the same data, but a quantitative metric for memory utilization could provide better insights. Understanding the amount of memory saved through Ivy’s approach would help assess its efficiency compared to traditional message-passing models.

Causes of Performance Degradation

The paper notes that performance curves flatten or degrade due to process migration overhead and false sharing.

-

Process migration occurs when a process moves between nodes, requiring memory transfers that can cause delays.

-

False sharing happens when multiple processors frequently access the same memory page, even if they are working on separate data within that page, leading to unnecessary invalidations and cache coherence traffic.

A useful improvement would have been software counters to track these slowdowns, allowing for a more detailed analysis of bottlenecks in Ivy’s performance.

Virtual Memory and Disaggregated Memory

Ivy’s use of virtual shared memory raises the question of how disaggregated memory architectures—where memory and compute resources are physically separated—might have improved its performance. Modern interconnects like PCIe Express Link could potentially reduce the latency of remote memory accesses, making Ivy’s shared memory model more practical in today’s hardware environments.

Could Hardware Modifications Improve Ivy?

Yes, hardware advancements could have significantly improved Ivy’s performance. Since the system relied on software-based shared virtual memory (SVM), many of its inefficiencies stemmed from high latency memory accesses, page migration overhead, and slow interconnects.

Potential Hardware Improvements:

- Faster Interconnects (e.g., PCIe Express Link)

-

Ivy used a 12 MB/s Apollo ring network, which became a major bottleneck.

-

Modern interconnects like PCIe Express Link or CXL (Compute Express Link) could drastically reduce memory access latency and improve bandwidth, making shared virtual memory much more viable.

-

Hardware-managed remote memory access (RMA) could eliminate some of the overhead caused by software-driven page migrations.

- Dedicated Hardware for Shared Memory Management

-

Ivy relied on software page fault handling, which was slow.

-

Hardware-based page migration and cache coherence mechanisms, like those found in NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Access) architectures, could have significantly reduced the overhead.

-

Specialized memory controllers could have handled page tracking and ownership resolution at the hardware level rather than relying on a centralized software manager.

- Improvements in Cache Coherence Mechanisms

-

Ivy suffered from false sharing and excessive page invalidations.

-

Hardware-assisted coherence protocols, such as directory-based coherence or MOESI (Modified, Owner, Exclusive, Shared, Invalid) protocols, could have reduced unnecessary memory traffic.

Ahead of Its Time

Ivy was a pioneering system, introducing shared virtual memory at a time when hardware was not yet mature enough to fully support it.

-

The concept of distributed shared memory (DSM) later re-emerged in systems like TreadMarks (1989) and modern far-memory architectures.

-

Had Ivy been implemented on modern hardware with high-speed interconnects, memory disaggregation, and improved cache coherence, it could have been a viable alternative to message-passing models.

Ultimately, Ivy did not receive the implementation it truly deserved at the time due to hardware limitations. However, its core ideas remain relevant in today’s discussions on distributed memory, disaggregated computing, and heterogeneous architectures.

Ivy’s Industry Adoption and Modern Relevance

Not Adopted in Industry, but Still Used in Research

Ivy’s shared virtual memory model was never widely adopted in industry. Instead, the industry moved towards message-passing architectures, which became the dominant paradigm in high-performance computing (HPC) and distributed systems. However, researchers continue to explore shared virtual memory concepts, particularly in the context of far memory and disaggregated memory architectures.

Far Memory and Modern Trends

One of the key takeaways from Ivy’s design is that it used virtual memory numbers to trigger software-based page faults, a mechanism that could have been implemented in hardware for better performance. This tradeoff between software vs. hardware page fault handling remains relevant today, particularly as far memory architectures gain traction.

Far memory architectures aim to:

-

Reduce page thrashing by allowing memory to be shared across multiple nodes with minimal migration overhead.

-

Leverage fast interconnects (e.g., CXL, PCIe Express Link) to provide low-latency memory access.

Trade-offs in Software Page Fault Handling

Ivy’s software-based page fault handler provided flexibility but introduced additional overhead. A key advantage of software page fault handling is that the CPU can perform other work while waiting for a page to be fetched—a feature that modern operating systems, such as Linux, continue to leverage.

However, Ivy’s implementation had limitations:

-

Write protection was supported, but there was no mechanism to update read protection dynamically, relying entirely on hardware mechanisms.

-

There was a plan to implement read protection updates, but it was never completed in the Ivy prototype.

Lessons for Modern Systems

-

Balancing software and hardware implementations is crucial. While software page fault handling provides flexibility, hardware-assisted page fault resolution (as seen in modern NUMA and memory-disaggregated systems) can drastically improve performance.

-

Buffering techniques can reduce page faults, but they introduce data staleness issues, which must be managed carefully in consistency models.

-

The core challenges Ivy faced—efficient memory access, process migration, and minimizing false sharing—are still relevant today, particularly as researchers explore disaggregated memory architectures.

TreadMarks: A Distributed Shared Memory System Similar to Ivy

TreadMarks, released in 1989, is a distributed shared memory (DSM) system designed for standard workstations and operating systems, particularly Unix-based systems.

How TreadMarks Compares to Ivy

-

Conceptually Similar: Like Ivy, TreadMarks provides a shared virtual memory abstraction for loosely coupled multiprocessors.

-

Key Difference: Unlike Ivy, which was implemented on Apollo workstations with a ring network, TreadMarks was designed to work on commodity Unix-based workstations connected via standard networking.

-

Lack of Citation: Interestingly, TreadMarks does not cite the Ivy paper, despite their similarities in approach. This could be due to independent development or a lack of awareness about Ivy’s contributions at the time.

Significance of TreadMarks

TreadMarks became one of the more well-known DSM implementations, demonstrating that distributed shared memory could be implemented on standard hardware and operating systems rather than requiring specialized architectures. While neither Ivy nor TreadMarks saw widespread industrial adoption, the ideas explored in these systems continue to inform modern research in far memory, memory disaggregation, and distributed computing.

Memory Allocation and Process Blocking in Ivy

System-Level Lock for Memory Allocation

Ivy enforces a system-wide lock for memory allocation, meaning that only one processor can allocate memory at a time. When a processor gains the lock, all other processors attempting to allocate memory must wait until the lock is released, effectively blocking their execution during this time.

Why is Locking Necessary?

Since Ivy uses a shared virtual address space, proper synchronization is required to prevent multiple processors from allocating the same memory region simultaneously. Without locking, two processors could:

-

Allocate overlapping memory regions, causing memory corruption.

-

Map to the same virtual address, leading to incorrect writes and inconsistency in the shared memory system.

-

Trigger race conditions, making it difficult to maintain coherence across nodes.

By serializing memory allocation with a global lock, Ivy ensures correctness but introduces a performance bottleneck, particularly as the number of processors increases.

Impact of the Apollo Ring Network

Ivy was implemented on an Apollo ring network with a bandwidth of 12 MB/s, which was relatively slow even for its time. This limited bandwidth exacerbated the performance overhead caused by:

-

Global memory allocation locks, which forced processors to wait rather than proceeding with execution.

-

Memory page transfers, which had to traverse the ring network, further slowing down the allocation process.

In modern systems, such bottlenecks are mitigated by NUMA-aware memory allocation, distributed memory management, and high-bandwidth interconnects like PCIe, CXL, and Infiniband.

Typical Use Case for Ivy and Apollo Workstations

Ivy was designed for workstations rather than large-scale supercomputers. It was implemented on Apollo workstations, which were primarily used by engineering and CAD (Computer-Aided Design) professionals. Major Apollo customers included:

-

Mentor Graphics

-

Ford

-

General Motors

-

Boeing

These industries required high-performance computing for design, modeling, and simulation, making Ivy’s shared virtual memory approach appealing for parallel processing workloads on distributed workstations.

Industry Context: Custom vs. Commodity HPC

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the industry saw a divide in high-performance computing (HPC):

-

Custom-built supercomputers dominated the HPC landscape.

-

Researchers and engineers began exploring commodity-based HPC clusters as a lower-cost alternative.

Ivy represented one approach to enabling commodity-based HPC, leveraging distributed shared memory across standard workstations instead of relying on expensive custom-built supercomputers.

Message Passing vs. Shared Virtual Memory

A key question at the time was whether shared virtual memory (SVM) (as seen in Ivy) or message-passing models (such as MPI) would be more effective for commodity-based HPC.

This discussion eventually led to the Beowulf cluster model, which emerged in the 1990s.

-

Beowulf clusters used commodity hardware connected via message passing networks instead of shared virtual memory.

-

Message passing became the dominant paradigm in distributed computing, largely due to its scalability and lower overhead compared to SVM.

While Ivy’s shared virtual memory model was ahead of its time, it ultimately did not become the standard for HPC, as message-passing techniques proved to be more efficient and scalable for large distributed systems.

Apollo Ring Network and Alternative Interconnects

Was the Apollo Ring Network Unidirectional?

Yes, the Apollo ring network used in Ivy was a token-based ring, meaning that data traveled in one direction around the network. This is similar to a relay race, where a token (message) is passed from one node to the next in a circular fashion.

Comparison with Other Network Topologies

-

Token Ring: Used in Apollo’s implementation. A single token circulates, and only the node holding the token can transmit.

-

Ethernet: Uses a shared medium where multiple nodes can attempt to transmit simultaneously, requiring collision detection and retransmission.

-

Bus Network: A single shared communication channel where all nodes can hear transmissions, leading to congestion at high loads.

-

Mesh Network: Nodes are connected in a grid-like structure, allowing direct communication between neighbors (North, South, East, West).

-

Torus Network: A grid network wrapped into a ring-like topology, reducing hop distance and improving communication latency.

-

High Radix Networks: Networks with many connections per node, improving performance but expensive and difficult to implement due to wiring constraints.

-

Dragonfly Network: A hybrid of high-radix and low-diameter networks, used in modern supercomputers to minimize hop count.

Why the Ring Network was a Poor Choice for Ivy

The ring topology used in Apollo’s implementation was a bottleneck because:

-

It did not scale well as more nodes were added.

-

It forced all traffic to flow in a single direction, leading to delays.

-

A single point of failure could disrupt the entire network.

Modern Networks and Ivy’s Relevance

Most modern supercomputers use a combination of high-radix and mesh-based interconnects, optimizing bandwidth and reducing hop count for communication.

-

The PlayStation 3 (PS3) used a ring network for its interconnect but with higher bandwidth, making it more efficient than the Apollo ring network.

-

Ivy itself was not dependent on the ring network; it was simply implemented on one. Had it been deployed on a more scalable network topology (e.g., mesh or torus), performance could have been significantly improved.

Key Takeaways

-

The Apollo ring network was unidirectional, making it a poor choice for scaling Ivy.

-

Mesh and torus networks would have provided better performance.

-

Modern HPC systems use hybrid interconnects, such as Dragonfly, to minimize latency and maximize bandwidth.

-

Ivy’s shared virtual memory model was limited more by its network implementation than by its fundamental design.

Evaluation of Ivy in the Context of CS Research

CS Research in the 1980s vs. Today

The bar for publishing computer science research was lower in the 1980s compared to today.

-

There were fewer competitors in shared memory research, making Ivy a remarkable contribution at the time, though not revolutionary by today’s standards.

-

If submitted today, the Ivy paper would likely be rejected, as modern research demands rigorous comparisons with alternative approaches and more extensive performance evaluations.

-

CS students today have fewer “low-hanging fruit” problems to tackle, as many foundational ideas in parallel computing, distributed systems, and memory architectures have already been explored.

Ivy’s Main Weakness: Lack of Comparison with Message Passing

One of Ivy’s biggest shortcomings is that it does not compare its performance against message-passing techniques, which later became the dominant model for distributed computing (e.g., MPI). Without such a comparison, it’s difficult to assess whether Ivy’s shared virtual memory approach was truly superior for real-world workloads.

How Does Rust Play Into This?

While the Ivy paper predates Rust, modern Rust-based systems programming offers features that could mitigate some of Ivy’s weaknesses, particularly in memory safety and concurrency:

-

Rust’s ownership model could help eliminate race conditions and ensure safe access to shared memory without requiring a centralized manager.

-

Rust’s async and multi-threading features could help in designing more efficient distributed shared memory (DSM) systems with reduced overhead.

-

Rust’s low-level control and performance optimizations make it well-suited for high-performance distributed systems, which Ivy aimed to be.

While Ivy’s design was ahead of its time, it suffered from high overhead and poor scalability. Modern techniques—including better interconnects, Rust-based concurrency management, and message-passing optimizations—would likely yield a more efficient implementation of a similar concept today.

Source

- IVY: A Shared Virtual Memory System for Parallel Computing. https://systems.cs.columbia.edu/ds2-class/papers/li-ivy.pdf

- https://www.eecg.toronto.edu/~amza/ece1747h/papers/treadmarks94.pdf